Field reports from Biloxi, Miss.*

It’s 9 a.m. and the steps to The Micah Center are full of people, waiting. It’s been unusually cold here for January, and a day since anyone could get a shower.

Here, the homeless of Biloxi can get a shower, pick up toiletries and socks and other clothing staples, and sit down for a cup of coffee and some donated sweet snacks for a few hours.

This morning, 23 men and women do. Dips down into the thirties means Gulfport opened an emergency cold-weather shelter, says Gary, who has been homeless for seven years. The people streaming in have taken a bus to the soup kitchen for a morning meal, then walked her, or are congregating from other parts of the downtown.

Dan Martin ’16 and I are at the door to the showers, with clear directions from Ms. Ethel. We call their number in order and they get 15 minutes in a private shower with bathroom.

Or, as she says, “15 minutes of privacy.”

That sticks with me as we put on the timers above the laundry machines, always going with the mesh bags they drop off to retrieve two days later: 15 minutes of privacy.

This is the only time they probably do get privacy — to be naked, to wash, to just have time away from anyone else, and most often, not in public.

It is the first window into our reminders of what we take for granted having stable housing. A bed. Clothes. Deciding how long we want to shower.

When the room is full, we replace empty coffee pots with full, explain to the few new people how this whole thing works, and mostly, I stand at the door making small talk with the clients but wishing there weren’t so many — so I could go sit next to a few and just talk. Listen.

Sydney introduces himself and says thanks. He also says he understands if we don’t like to shake his hand. I’m reminded how often people dismiss homeless as non-entities, and I am sad he’s thinking of that, even in here.

Julie thanks us for being here, and Cool C wants us to know he’s a leader and doing his own thing. He’s been a little loud today and Suzanne, who is a three-month volunteer, has to remind him to keep it down. Respect everyone’s space, Cool C, she says.

Dan and I take laundry tickets and carefully load small piles of laundry into recycled plastic bags for clients. A few shirts. For Mason, it is a single pair of pants. I want to see Mason because I hope he has a giant backpack full of other clothes when he rolls in. He does not come.

We knock and politely let each person know when they have 5 minutes left in the shower, then speed clean the room — spritzes of sanitizers in the shower, wiping any hairs and flushing toilets if need be and getting it new for the next person, ASAP.

There’s a lot going on. We like it.

“It opens your eyes of what you take for granted every day, that we have laundry, food and shelter accessible,” says Dan, a college student. “You have different choices in clothing. I’m seeing the bags they have and it’s what they have in their life to use and to wear. It really opens my eyes into how they have to live and how they have to adapt to live. This place provides laundry and showers, and ability to get away from it for a morning, for a couple of mornings a week — to have a cup of coffee and talk with people.”

The Micah Center is a social outlet for homeless, says Gary. For five of his seven years without a home, he’s camped near the Back Bay Mission and Micach Center, and volunteers regularly at another outreach program. He also serves on several homeless-advocacy boards, lending a hand with many things with his background in business. He used to run a beauty supply company.

“I walked away from my life,” he tells me. He struggles with severe depression.

The center, he says, is indeed a social place, and offers people the handouts that are needed, like a shower and socks, as well as resume training and ways to transition out of homeless— a tough thing to do. He wants people to know that there are “normal” people who are homeless — not all drug addicts and panhandlers people often see.

In Biloxi, Katrina, the BP oil spill and a host of other factors lend to homelessness. There are no permanent shelters. That’s what makes Miach so important; it’s a permanent assistance and safe place.

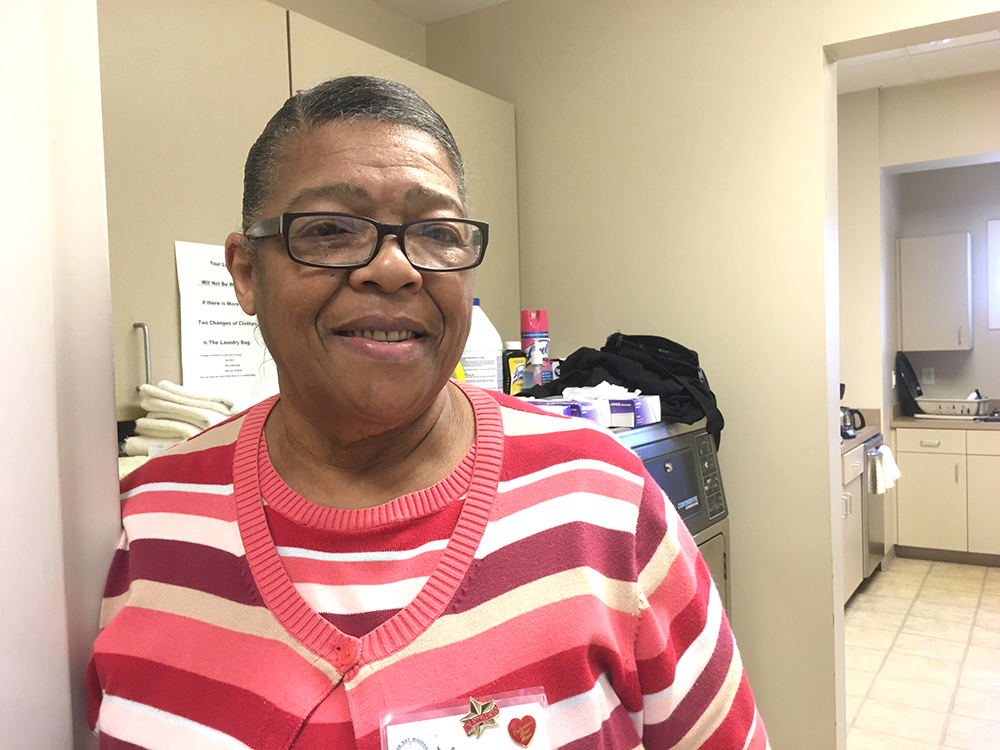

When we go, Suzanne will be here another two months. Ethel, from Biloxi, is a full-time volunteer. She comes here four days a week, for six years. She knows how valuable such help is. She lost everything in Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and lived with a family who hosted her in Florida through a church until a FEMA trailer was available.

“I wanted to give back because people have done a lot for me,” she says, “because I, too, was homeless after Katrina.”